“Da agricoltore, soltanto da Agricoltore” (“As a Farmer, Only as a Farmer.”)

31 January, 2025

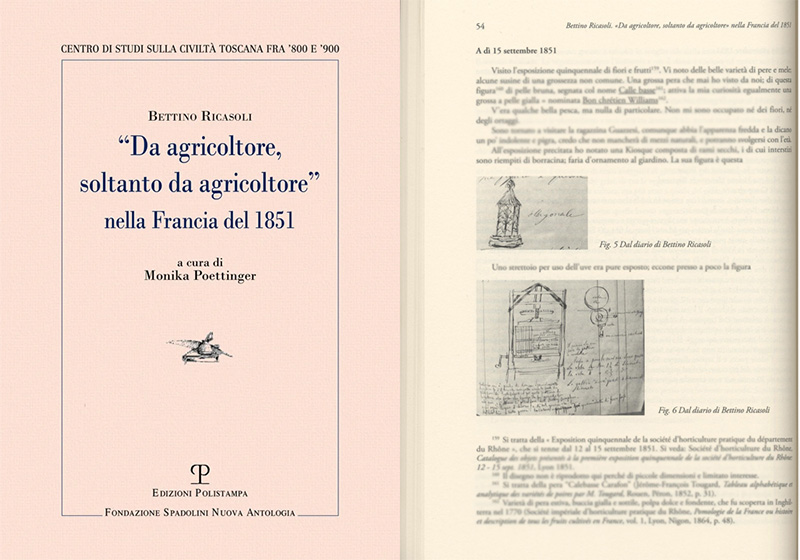

On October 30th, the Circolo dell’Unione (Union Circle) in Florence hosted the presentation of the book Da Agricoltore, soltanto da agricoltore (“As a Farmer, Only as a Farmer”) in 1851 France, edited by Monika Poettinger and published by Polistampa.

The book tells the story of Bettino Ricasoli‘s journey in 1851, a key figure in the history of Italian agriculture and the emerging Kingdom of Italy, as he travels through France to attend the Great Exhibition in London.

After holding an important political office (he had served as Mayor of Florence until 1848) and spending a brief period in Switzerland, Baron Ricasoli returned to Castello di Brolio to retire with his family. There, he discovered that his wines had lost their competitiveness compared to the renowned French wines. He therefore decided to embark on an exploratory journey through several French wine regions, carefully observing local agricultural and winemaking techniques. His aim was to improve the quality of his wines, make them competitive with foreign products, and enhance their preservation during export.

The book delves into the historical and socio-economic context of 19th-century rural France, contrasting it with the challenging conditions of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. It details the obstacles, such as adverse weather and vine diseases (like phylloxera), and the opportunities faced by French farmers, recorded with remarkable precision in a travel diary that Ricasoli kept as he toured the vineyards of Bordeaux, Médoc, Gironde, Beaujolais, and finally Burgundy. It was in Burgundy that Baron Ricasoli found the greatest alignment with his own vision of viticulture and winemaking. There, through tastings, he identified what he described as the “perfect wine,” which he would strive to recreate with relentless dedication at Brolio.

Poettinger highlights how these experiences influenced both Ricasoli’s agricultural practices and his political ideas. On the one hand, he introduced new technologies and methods to his estate in Tuscany; on the other, he developed social and professional networks, emphasizing the importance of international connections for agricultural progress.

What stands out most, however, is the author’s ability to convey Bettino Ricasoli’s passion for agriculture and his unwavering commitment to improving the conditions of farmers and the quality of his wines. This commitment would culminate, twenty years later and after countless experiments, in the formulation of a “recipe” for producing high-quality Chianti. A recipe that, with remarkable foresight, became his most significant legacy to his family and to the winemaking tradition of Tuscany.