Brolio Wines on Historical Menus

30 September, 2024

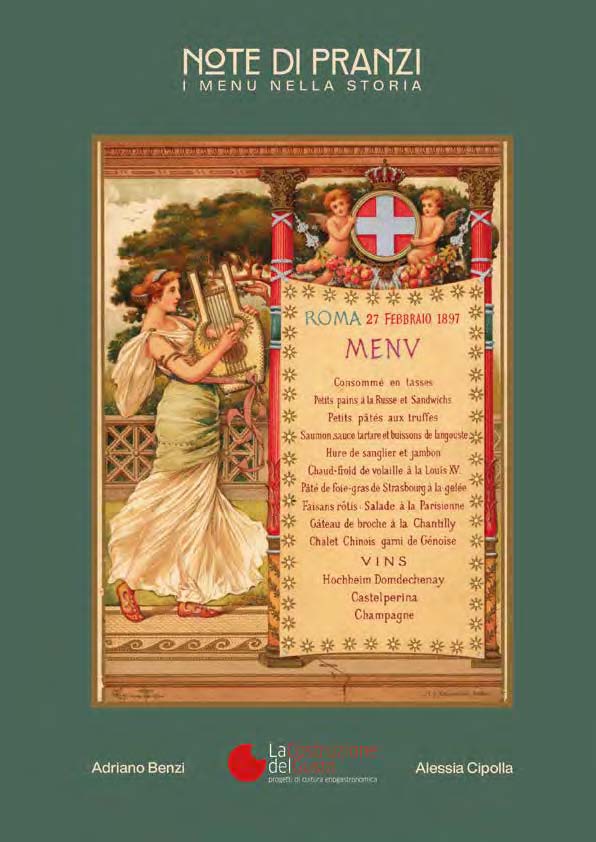

“Note di Pranzi” (Notes of Lunches), the term Artusi used for menus, is an exhibition curated by architect and culinary historian Alessia Cipolla. It offers a fascinating overview of the evolution of menus from their inception in the early 1800s to the present day. First presented in Treviso in the spring of 2023, the exhibition displays 400 pieces selected from the collection of Piedmontese entrepreneur Adriano Benzi, organized into five thematic categories: royal, convivial, travel, artist, and restaurant & hotel menus.

The modern concept of the menu originated in the early 19th century and was shaped by two significant events that occurred in Paris: the introduction of “Russian style” service and the emergence of the first restaurants. Prior to 1810, “French-style” service required all courses to be presented simultaneously. The innovation of “Russian style” service, named in honor of the diplomat Alexandre Boris Kourakin who first introduced it at his receptions, involved serving dishes in sequence and already portioned. This made the presence of a list of courses necessary.

According to Alessia Cipolla, “Menus have never been merely lists of dishes; they are historical documents that reflect the gastronomic and cultural trends of their time. The exhibition illustrates how menus provide insight not only into the evolution of taste and cuisine but also into the history of illustration, paper, printing, and much more. Often, in addition to the food listings, menus included the musical programme of the banquet, the dance card, or the seating plan. Thus, reading these historical menus today reveals much about their era.”

The emergence of restaurants in Paris at the end of the 18th century marked another turning point in gastronomic culture. Initially informal establishments where the chef served whatever was available, they gradually became more sophisticated, allowing customers to choose from various courses and transforming the meal into a personalized experience. Menus evolved into a means for chefs to highlight their creativity and for restaurants to express their identity.

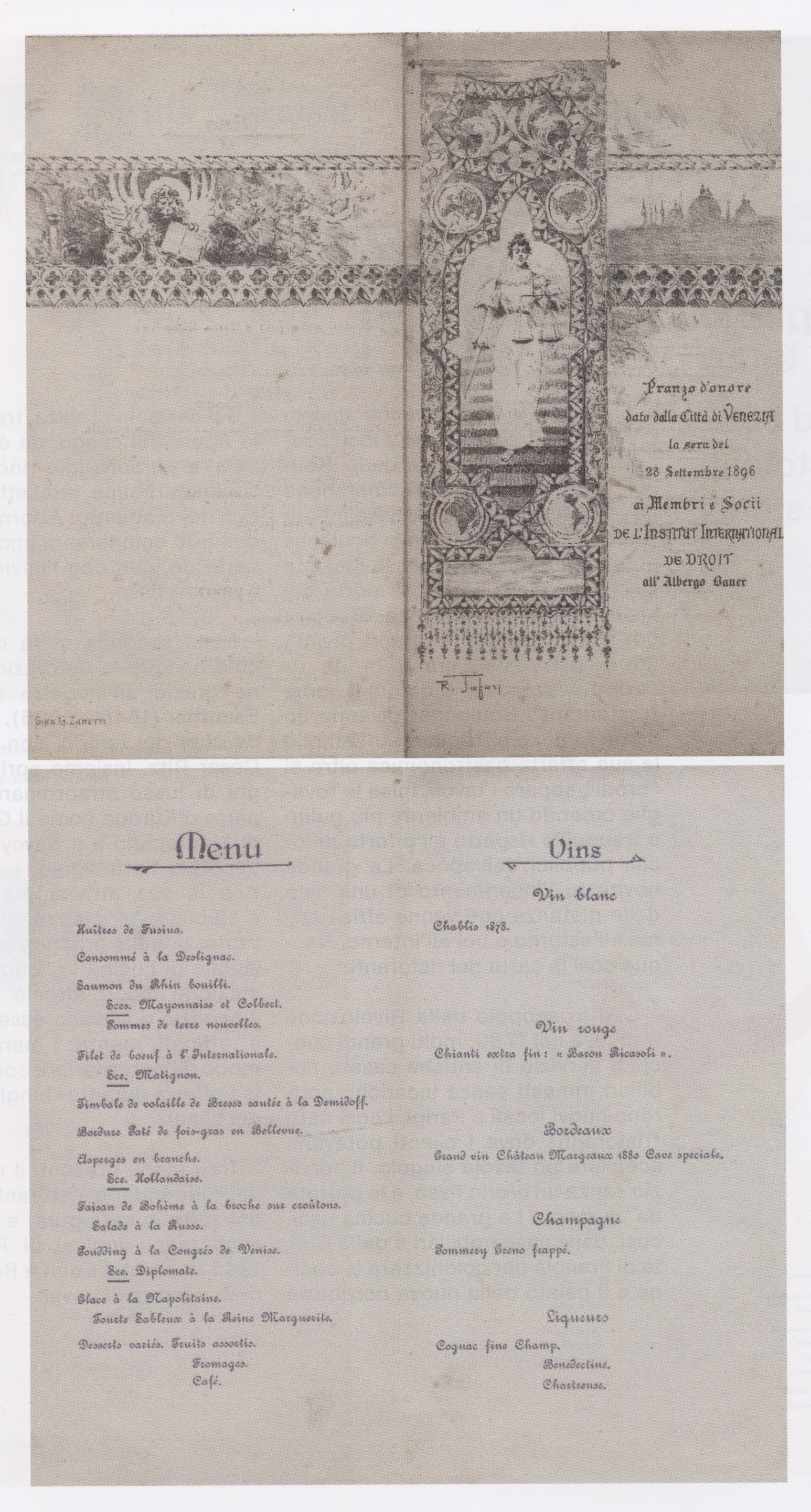

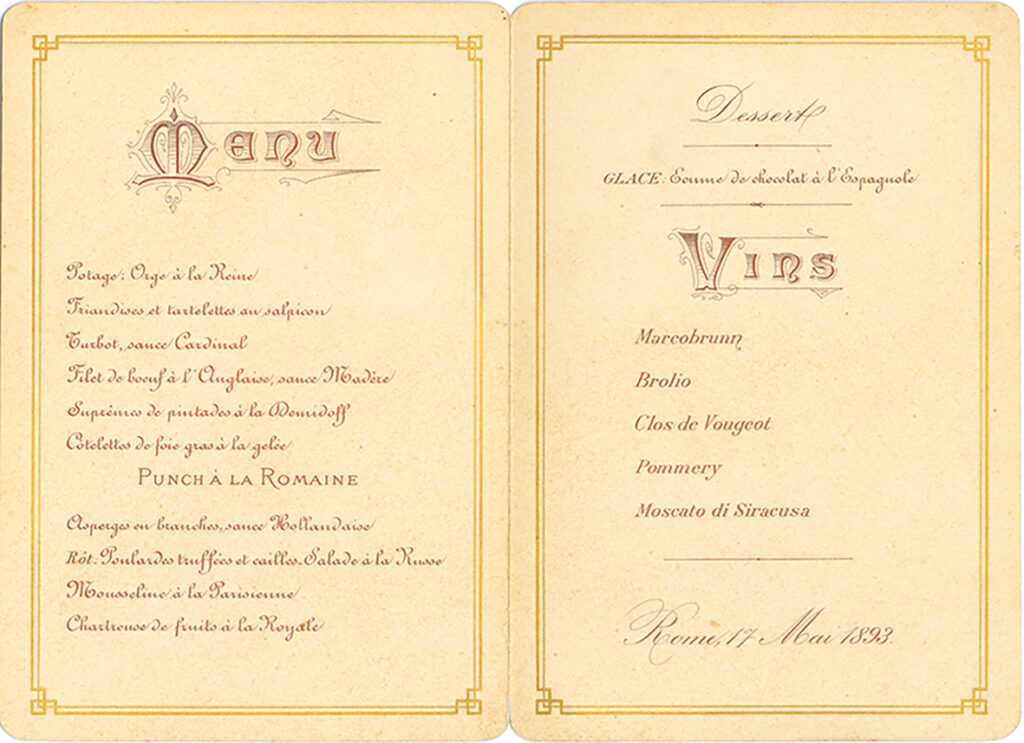

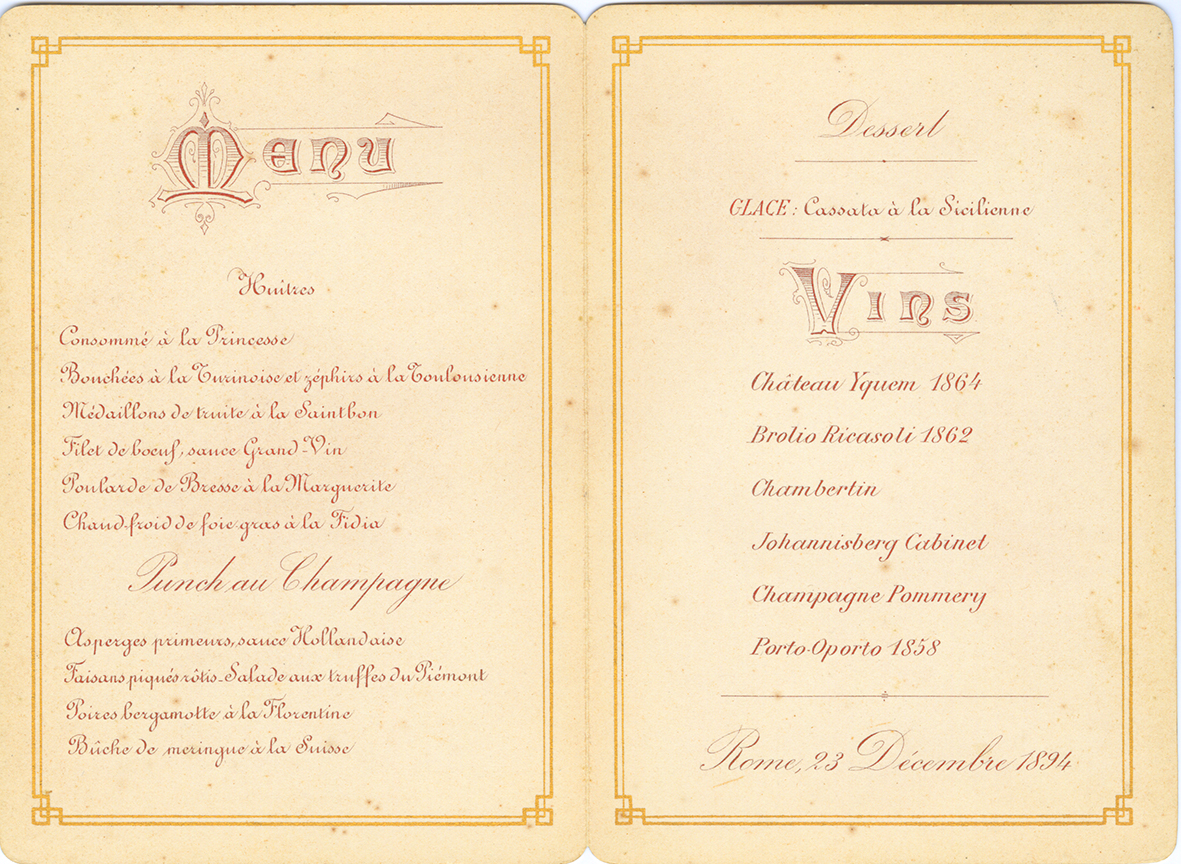

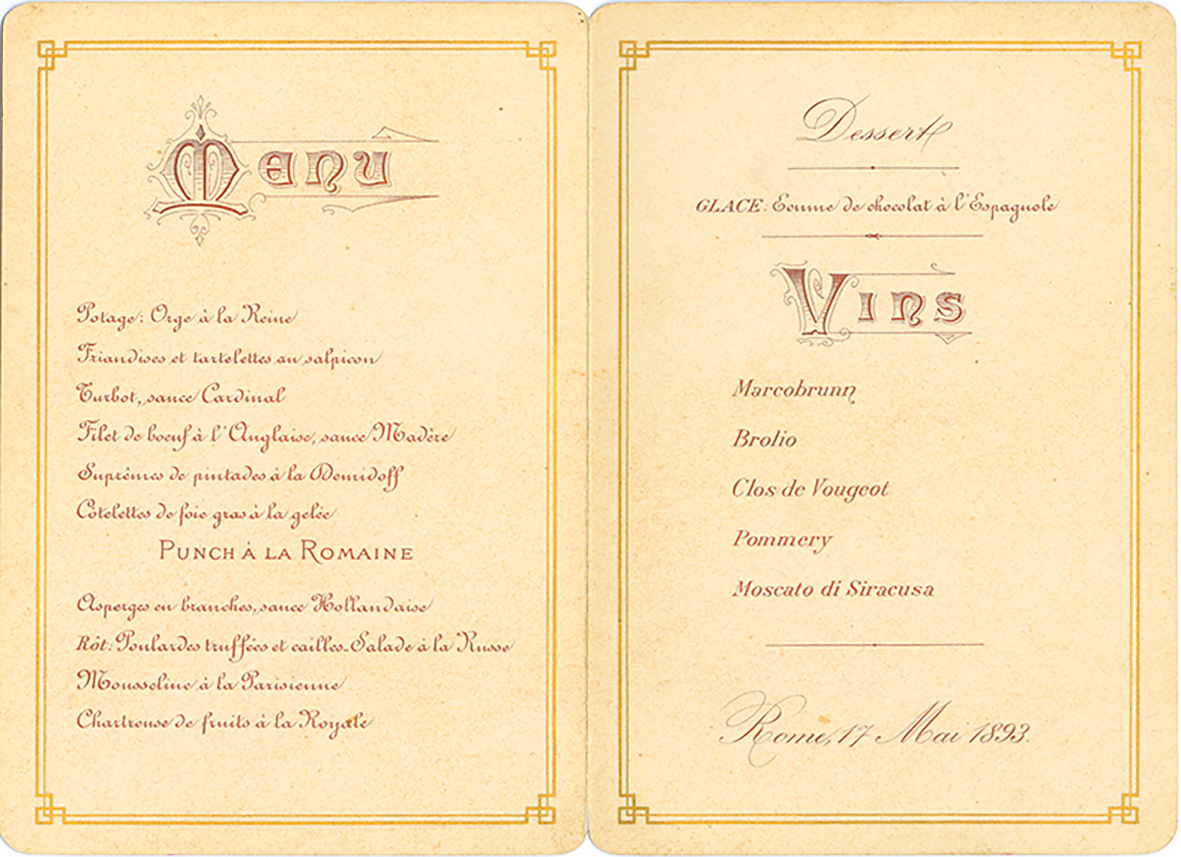

In the royal menus section, the curator highlighted the presence of Brolio wines on the menus of several royal receptions in the Kingdom of Italy under King Umberto I (1878-1900). This reflects the influence of Bettino Ricasoli and the recognized quality of his wines, which were explicitly mentioned on court menus—often the only Italian wines alongside prestigious foreign labels, particularly French ones. A notable example is the menu from a gala dinner at the Hotel Bauer in Venice in 1896, where Ricasoli wines played a prominent role, underscoring their importance and appreciation in the art of receptions. It is also noteworthy that Brolio wines were often boldly and innovatively paired with fish dishes.

Currently, a re-edition of the “Note di Pranzi” exhibition is being prepared, which will be staged in Verona during Vinitaly in spring 2025, with the aim of inspiring greater awareness of the art of dining and the stories behind each menu.